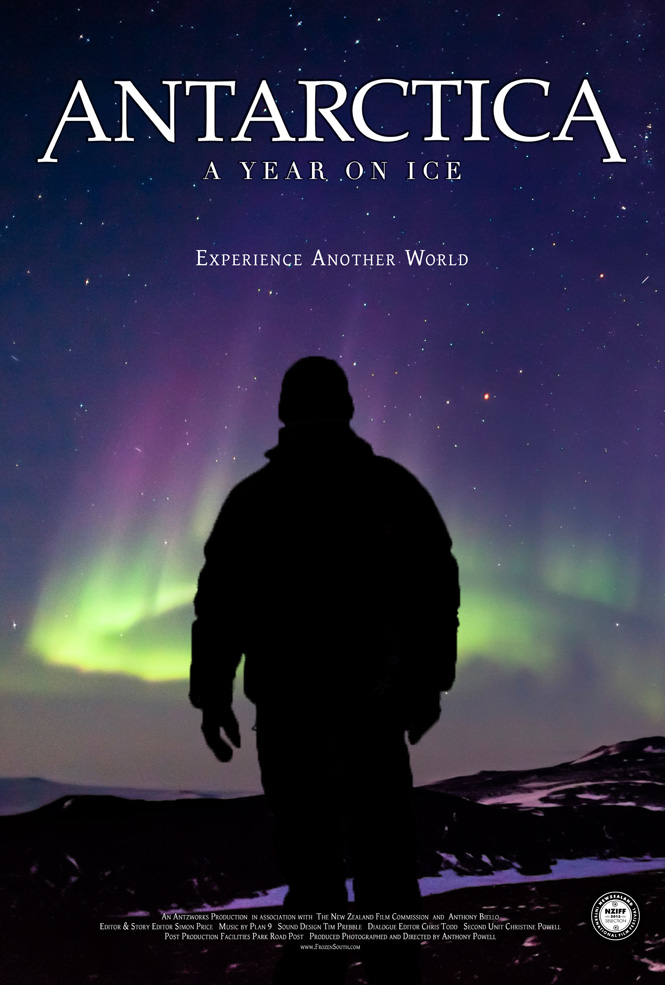

Recently I was introduced to photographer and filmmaker Anthony Powell, whose first feature-length documentary is being released today, November 28th, 2014, in the United States. Antarctica, A Year on Ice is a visually stunning exploration of what it is like to live on the seventh continent for a full year, including the dark, harsh, never-before-captured winters.

Having world-premiered in New Zealand last summer, the film made quite a splash at film festivals and garnered beaucoup awards, including 11 for “Best Documentary” and five for cinematography, among others. I don’t know about you, but I’m pretty excited to see it. Here’s the trailer:

The film was primarily shot in the Ross Island area of Antarctica, home to the U.S. McMurdo research station and New Zealand’s Scott Base. At this latitude, the bases experience four months of continuous sunlight between October and February and four months of darkness from late April to late August. During the six-month-long winter, planes cannot come or go and the staff are cut off from the outside world.

Thirty countries operate seasonal and/or year-round research stations on Antarctica.

About the Filmmaker

Anthony Powell grew up in Taranaki, New Zealand. He began working in Antarctica in 1998, as a Communications Tech at Scott Base. He has spent more than 100 months in Antarctica over the years. He even got married there in 2003, to an American named Christine who was working at McMurdo Station.

Anthony had to design and build many of the camera systems utilized in the film due to the extreme conditions in which he worked. Although this is his first film, Anthony has contributed to numerous television shows, films, and magazines, including the BBC’s Frozen Planet series, which won an Emmy Award for photography. He also received the National Science Foundation Artists and Writers Award, which allowed him to spend a summer season filming full-time in Antarctica.

Q&A with Photographer/Director Anthony Powell

Due to Anthony’s busy travel schedule, he didn’t have time to do a 1:1 interview with me before the film’s U.S. release. He did, however, give me access to the film’s press materials, which included the following questions:

Antarctica is often called the coldest, windiest, driest place on the planet. We’ve heard about the cold – how does the wind and dryness affect you?

The wind is harder to get used to than the cold. You can dress for the cold easily enough, but when you add the wind, any slightest gap in your clothing becomes painfully apparent very fast. I failed to tuck my glove in properly one time, and in the time it took me to walk between buildings, I had frozen a patch of skin on my wrist that came up in a row of blisters.

The dryness was quite unexpected. Because the air temperature is almost always below freezing, there is no moisture in the air. This means most people need to use a moisturizer of some kind. The other side effect of being so dry is lots of static electricity. People are constantly getting shocked reaching for door handles or light switches, or shocking each other. It also means bad news for electronics that are constantly getting zapped by the static when people open their computer or pick up a phone. The static discharge will ruin computer chips.

What’s the hardest thing about living there?

I’d say just the isolation from friends and family back home; missing out on family events. Especially during the winter when we are isolated from the rest of the world for six months with no way out. If something goes wrong at home during the winter, you have no way of being with your family, you are stuck there.

Also, nutritionally it can be difficult. There are no fresh fruits or vegetables for nearly six months in winter. A small greenhouse can provide a very small green salad once a week if it is running, but even that is not guaranteed.

Conversely, in many ways one of the best things about being there is the isolation. You are suddenly free from media bombardment and advertising. You have all the noise of modern society removed, and you get to concentrate on the simple pleasures of life again.

Aurora Astralis over Black Island Station, the Antarctic communication center

How would you describe the feeling of being in Antarctica?

Once you are away from the noise of the base you can experience absolute silence, there is no noise other than your own breathing. The absolute emptiness, knowing there are no other people for hundreds of kilometers in any direction.

How do you think living on the ice has changed you?

In some ways it’s a bit like going and living in a monastery for a while. It gives you a very different perspective on your life back home. You go down there with just a couple of suitcases, and you really do have very few possessions, and it’s great. All the clutter, all the noise, all the expectations of modern society are removed. Less can be so much more.

You get to focus on the important things in life, which ultimately are other people. You also learn to have a great appreciation for the little things in life: a fresh piece of fruit, rain, playing with a pet, walking barefoot in the grass.

How did you come up with the idea of producing this documentary and why did it take you so long?

I initially started shooting time-lapse when digital cameras got to the point where you could take a still photo that would hold up on a big screen, and was amazed at how well it brought the landscape to life. You can normally sense the things going on around you, but not see them.

The first few years was just building up more and more footage, as well as inventing systems that could still work in the extreme cold of winter. Often what is on the screen for a few seconds took me days or sometimes even months to capture.

Once I felt I had enough material to show the changing seasons of nature, then I concentrated on filming the people more and telling the story to hold the rest of the visuals together. Of course the other reason it took so long to make is because I was filming in my spare time. By the time you get done with the normal busy work day, there is not a huge amount of time left over.

Polar Stratospheric Clouds or Nacreous Clouds form at an altitude of about 16 km up in the sky when the thin layer of ozone depleting gasses freeze and form crystals when the air temperatures reach approx -80c or more. This creates the catalytic reaction that eats away at the ozone.

What makes Antarctica, A Year on Ice different?

Firstly, this film has very much an insider’s point of view, told from the perspective of the everyday workers: the mechanics, technicians, cargo handlers, carpenters, electricians, cleaners and cooks, the people who keep the bases running, everyday people that are very relatable. Because it is has been made by an insider, it also means unparalleled levels of access to places and people.

Secondly, the footage has been meticulously gathered for over 10 years, including 9 winters. Most visiting film crews only come down for a few weeks during the short summer season, which is only a tiny fraction of the full experience. Imagine if a film crew could only film in your home town for the summer holidays. They would only be getting a very limited view of what it is like to live there. For the first time, audiences get to experience the full year-round experience of life in Antarctica.

What’s next for you as a filmmaker?

I have a few projects I’m working on. First up is a series on online mini documentaries that will be both entertaining to the general public and provide a free teaching resource for schools, etc. I’m also gathering a lot of new cutting edge interactive material like full spherical 360 degree video.

I’m going to be filming a new Antarctic TV series at the same time as the mini documentaries.

For my next feature film I am collaborating with a group of handpicked photographers from around the world, to produce a film that covers all seven continents and tells more of a global story. We are still in the early stages, but have already got about 70% of the footage ready to go between us. The final film will utilize a variety of both traditional and new cutting-edge camera techniques.

Emperor Penguin in Antarctica. “Often penguins will approach us because they are curious, and we will just sit still until they move on. We try to have as little impact as possible, to keep things as natural as possible,” Powell says.

If I get a chance to talk to Anthony in the future, do you have any questions you’d like me to ask him? Let me know in the comments.

For screening times and locations for Antarctica, A Year on Ice, please visit Music Box Film’s website. For more information, please visit the film’s official website, Facebook page, or Youtube channel. Also, to purchase photos from Anthony’s Antarctic gallery, see AntarcticImages.com.

Cheers,